Origins of The Mandala

Nature

Courtesy Credit: rgbstock.com

Courtesy Credit: rgbstock.com

When you think of Mother Nature, graceful, rounded forms come to mind. She is, of course, the origin or mother to Mandalas. Curves, arcs, coils, circles, and spirals are expressed as buds, tendrils, seeds, bubbles, flowers, nests and so much more. From the cycles of the days and seasons to the physical details of plants and animals, from the microcosm of a cell to the macrocosm of the solar system, it is all variations on a single circular theme, beautiful in all its variety. In our workshops we will explore this natural organizing principle more deeply, even to the mechanics of natural movement.

India

Credit: Buddha Dharma Education Association

Credit: Buddha Dharma Education Association

Although the word Mandala is used in an almost generic way today to describe circular designs, the word itself comes to us from the ancient Hindu language of Sanskrit. Its meaning, literally, is “container of sacred essence”. As you study Mandalas more and more, you will come to realize the truth of this definition! It is particularly apt when you consider the sacred architecture of the stupa (temple).

The traditional and familiar form of the structured or geometric Mandala,

as we know it today, also originated in India. It is most often associated with Buddhism since creating Mandalas for enlightenment was taught by Siddhartha Gautama, known as the Buddha, in the 6th century B.C. However, in India the histories of Buddhism and Hinduism are closely linked, and the Mandala is part of Hindu spiritual practice, as well. Truth be told, Mandalas began in India long before current labels for religious practice even existed. In India’s pre-history,

a Mandala was not even visual art at all. This intriguing and surprising origin is something we explore more

in the workshops.

The traditional and familiar form of the structured or geometric Mandala,

as we know it today, also originated in India. It is most often associated with Buddhism since creating Mandalas for enlightenment was taught by Siddhartha Gautama, known as the Buddha, in the 6th century B.C. However, in India the histories of Buddhism and Hinduism are closely linked, and the Mandala is part of Hindu spiritual practice, as well. Truth be told, Mandalas began in India long before current labels for religious practice even existed. In India’s pre-history,

a Mandala was not even visual art at all. This intriguing and surprising origin is something we explore more

in the workshops.

Mandalas Around the World

The history of the Mandala is very rich. Besides India, many countries and cultures around the world have produced Mandalas. All have spiritual and healing functions as well as symbolism. Here are just a few of them.

Celtic

Celtic Mandala, Property of

Lily Mazurek

Celtic Mandala, Property of

Lily Mazurek

The most notable and best-loved feature of the Celtic designs is, of course, the amazing quality of line. Usually one unbroken line twirls and spirals into a multitude of patterns and figures. The repeated crossing of the line, over itself, was believed to increase protection and ward off evil. Perhaps it was hoped that evil would lose its way in the maze of loops! In a Celtic design called the “love knot”, the continuous flow of a single line symbolizes the path of true love, briefly wandering here and there for a while, but always returning home to the beginning. Other Mandala designs, such as those on tombstones or Celtic crosses symbolize the continuity of the cycles of life and the connectedness of all living things.

Christian

Credit: Cathedral of Strasbourg, France

Credit: Cathedral of Strasbourg, France

The Christian tradition is replete with Mandalas, from halos to architectural oculi, to rose windows. Then there is the marble paved pattern on the floor of the Chartres Cathedral in France, which is a Mandala design known as a labyrinth. It has been the primary inspiration for many labyrinths created in the last decade, particularly in the United States. Made with distinctive blue and white tiles laid in quadrants, this 12-circuit labyrinth was used for reflection and penance beginning in the 13th century. Amazingly, it is the same size and shape as the rose window above it. Why this was constructed in this way and the effect it has on people is something we will discuss in our workshops.

Islamic

Credit: www.Islamhoy.org

Credit: www.Islamhoy.org

In Islam, most sacred art consists of abstractions or geometric shapes, such as squares inside circles. It is understood that God is present in everything, so that

a specific representation of the Divine is not necessary and is even considered blasphemous. As with the Indian stupa, a holy mosque becomes a Mandala with

the dome representing the heavens and lifting people’s hearts and minds

toward Allah.

a specific representation of the Divine is not necessary and is even considered blasphemous. As with the Indian stupa, a holy mosque becomes a Mandala with

the dome representing the heavens and lifting people’s hearts and minds

toward Allah.

Jewish

Credit: Adam Rhine

Credit: Adam Rhine

The Star of David is probably the best known Jewish Mandala. It represents the

oneness and interconnectedness of all things, and the union of the feminine and

masculine. Temples, with their concentric walls and holy center, are also

Mandalas. Because visual images are prohibited in Judaism, it is difficult to find

Mandala art in the usual context. The Jewish Mandalas we find today are mainly

associated with the mystical tradition of the Kabbalah and are used for meditation

and contemplation such as the example you see here.

oneness and interconnectedness of all things, and the union of the feminine and

masculine. Temples, with their concentric walls and holy center, are also

Mandalas. Because visual images are prohibited in Judaism, it is difficult to find

Mandala art in the usual context. The Jewish Mandalas we find today are mainly

associated with the mystical tradition of the Kabbalah and are used for meditation

and contemplation such as the example you see here.

Navajo

Credit: miscellaneous-pics.blogspot.com

Credit: miscellaneous-pics.blogspot.com

In North America, the Navajo people produced some of the most interesting

Mandalas structures including sand paintings, dream catchers, and medicine

wheels. With the sand paintings, their symbolism included animals and forces of

nature. In the Level I Workshop we explore in more detail the fascinating how and

why of these native Mandalas produced by medicine men and women.

Mandalas structures including sand paintings, dream catchers, and medicine

wheels. With the sand paintings, their symbolism included animals and forces of

nature. In the Level I Workshop we explore in more detail the fascinating how and

why of these native Mandalas produced by medicine men and women.

Tibetan

Mandala created by Monks from the Drepung Loseling Monastery

Mandala created by Monks from the Drepung Loseling Monastery

Perhaps some of the best known Mandalas today are the beautiful designs made of

powdered marble and semi-precious stones, created by the Tibetan monks. The

Tibetan word for Mandala is kyil-kor, which means “center of the universe in which

a fully awakened being abides”. Again, the truth of this definition becomes more

evident, the more you create Mandalas and share information with others. In the

workshops we discuss the purpose of the Tibetan Mandala and specifically what it

represents to the monks who make them.

powdered marble and semi-precious stones, created by the Tibetan monks. The

Tibetan word for Mandala is kyil-kor, which means “center of the universe in which

a fully awakened being abides”. Again, the truth of this definition becomes more

evident, the more you create Mandalas and share information with others. In the

workshops we discuss the purpose of the Tibetan Mandala and specifically what it

represents to the monks who make them.

From East to West.....

Jungian

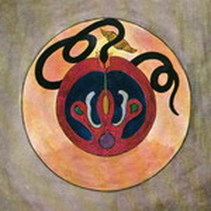

Collection of C.G. Jung

Collection of C.G. Jung

We can thank Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung for introducing the Mandala to

the western world. From his experiences and those of his patients, we have a

broader definition and a freer application of the Mandala than existed originally.

Jung championed the spontaneous Mandala in contrast to the preplanned,

geometric mandalas that existed previously in cultures around the world. Where

religious Mandalas often have a specified content and format, personal mandalas,

such as those fostered by Jung are unlimited in their style, format and symbols. We

knew that Mandalas represented the universe, but thanks to Jung, we now know

that they also represent the universe of the Self. The Mandalas we produce in our

Mandala Workshops tend to be more Jungian and organic in style than the one

found elsewhere around the world.

the western world. From his experiences and those of his patients, we have a

broader definition and a freer application of the Mandala than existed originally.

Jung championed the spontaneous Mandala in contrast to the preplanned,

geometric mandalas that existed previously in cultures around the world. Where

religious Mandalas often have a specified content and format, personal mandalas,

such as those fostered by Jung are unlimited in their style, format and symbols. We

knew that Mandalas represented the universe, but thanks to Jung, we now know

that they also represent the universe of the Self. The Mandalas we produce in our

Mandala Workshops tend to be more Jungian and organic in style than the one

found elsewhere around the world.

Copyright © 1996-2024 Lily R. Mazurek -- All Right Reserved -- Pembroke Pines, FL -- USA

No part of this website may be copied or used without written permission of Lily Mazurek.

To quote material, or use photos or content, please make your request to: mandalaworkshops at bell south dot net

No part of this website may be copied or used without written permission of Lily Mazurek.

To quote material, or use photos or content, please make your request to: mandalaworkshops at bell south dot net